Your votes are in!

Thanks to everyone who gave us your opinions on Postmodern buildings worthy of landmark designation.

Here are your top picks:

The Lipstick Building

60 Wall Street

The Paley Center for Media

Charles A. Dana Discovery Center, Central Park

Ballfields Cafe, Central Park

Four Seasons Hotel

U.S. Courthouse Annex

Islamic Cultural Center

110 East 64th Street

Worldwide Plaza Tower & Residences

This series generated lively discussions of pros and cons, thoughtful comments, and personal anecdotes that underscore the architectural and historic significance of these buildings to our City. As promised, we will let the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) know your favorite buildings and ask them to evaluate them for designation.

We hope this spurs LPC to consider Postmodern architecture more seriously and recognize that New York City residents would welcome the City government’s attention to designating architecture of the more recent past. New Yorkers have now lived with PoMo buildings for decades, appreciate them, and want them protected for the future.

Our selections came from a list of Architect Robert A.M. Stern’s favorite Postmodern buildings. If you want to suggest a building, Postmodern or otherwise, to LPC for consideration you can do so here.

Keep an eye out for our City’s future landmarks!

______________

Postmodern architecture has been with us since the early 1970s—pushing back against spare Modernism with sometimes fanciful use of historic architectural elements. New York has striking examples. But few have received landmark designation.

Noted architect Robert A.M. Stern has proposed a list of Postmodern buildings he deems worthy of designation.

______________

Below is a list of all the buildings and structures that were voted on.

Kevin Roche’s design for 60 Wall Street articulates the classical column with a Postmodern flair, crowning the 52-story tower with a capital of paired columns rendered from sets of bay windows supporting a classical pediment.

The City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission declined to landmark the fanciful, Egyptian-themed public atrium that Roche designed at 60 Wall Street, saying Postmodern architecture needed further study. The atrium has now been destroyed. There is an extensive body of work on this architecture and we don’t want to risk other losses.

We could still save the exterior of 60 Wall Street.

The “Lipstick Building” – 885 Third Avenue, Manhattan

(Philip Johnson & John Burgee, 1986)

Philip Johnson and John Burgee’s unorthodox and arresting design for the often-called “Lipstick Building,” a 34-story ellipse-shaped tower sheathed in bands of red-polished granite and stainless steel, gets its name from the telescoping upper floors that create a dynamic effect instantly likened to a lipstick emerging from its canister.

The Paley Center for Media (formerly the Museum of Television & Radio)

25 West 52nd Street, Manhattan (Philip Johnson, 1991)

Philip Johnson’s Museum of Television and Radio is a striking success of Postmodernism’s revival of tradition and classicism: its 16-story limestone facade features turrets and a small pediment above a rounded arch at street level and is capped with four matching turrets on the tower above, a respectful and sculptural Postmodern form.

Asia Society – 725 Park Avenue, Upper East Side Historic District

(Edward Larrabee Barnes, 1981)

The Asia Society building is a testament to Postmodernism’s desire to place new construction within its existing context. Its red Oklahoma granite façade follows the strong line of apartment buildings looming over Park Avenue and then is set back at the corner to allow for a subtler articulation on 70th Street that respects the neighboring historic brownstones.

Islamic Cultural Center – 1711 Third Avenue, Manhattan

(SOM, Michael McCarthy, 1991)

Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill’s Islamic Cultural Center is a Postmodern interpretation of the Islamic tradition of geometric—rather than figurative—architectural ornamentation. Rotated 29 degrees off the street grid to face Mecca, the eight-story mosque is clad in graying rose Stony Creek granite pierced by thin strips of glass. The copper-clad dome sits atop 12 large clerestory windows patterned with blue ceramic that recalls the blue tiles on the Great Mosque of Isfahan.

Storefront for Art and Architecture – 97 Kenmare Street, Manhattan

(Vito Acconci and Steven Holl, 1993)

A collaboration between artist Vito Acconci and architect Steven Holl, the elevation of the Storefront for Art and Architecture uses 10 pivoting panels of concrete board at various orientations to disrupt the distinction between the interior space of the gallery and the exterior space of the street. In this postmodern design, the façade becomes permeable.

Store facade at the Sherry-Netherland Hotel – 781 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan (Michael Graves & Associates, 1984) located within Upper East Side Historic District

Only the facade of Michael Graves’ first retail store still exists, next to the entrance of the Sherry-Netherland Hotel. A pink stone portal crowned by a golden Grecian vessel all set into a glass façade, the simplified design is a hallmark of Postmodernism’s classical revival that sticks out among the traditional and reserved designs of Fifth Avenue.

712 Fifth Avenue – At 56th Street

(KPF – Kohn Pedersen Fox, 1990)

712 Fifth Avenue towers above the landmark Fifth Avenue Rizzoli and Coty buildings, set back 50 feet from the Avenue so that its slender gray limestone and white marble silhouette appears to rise from a base of French neoclassical townhouses. As part of the development, a two-story jewelry store at 716 Fifth Avenue was replaced with a five-story neoclassical facade that matches the scale and style of the neighboring landmarks. What makes this building Postmodern is the play between the eclectic and historical buildings that form its base and the abstracted historical details on the 52-story tower, including massive granite quoins and a temple-like top.

The neoclassical facade at 716 Fifth Avenue, designed in 1986 by Beyer Blinder Belle, is an essential part of the Postmodern character of the tower at 712 Fifth Avenue, completing the historical base formed by the Rizzoli and Coty Buildings. Now, this Postmodern fabric is in danger: a proposal in front of the Landmarks Preservation Commission would strip 716 Fifth Avenue of its differentiated neoclassical limestone detailing and replace it with a contemporary travertine facade that matches the neighboring building at 718 Fifth Avenue. The proposed modification would destroy the Postmodern genius of 712 Fifth Avenue, defacing the subtly differentiated but cohesive historicist base that was designed to play off the abstract detailing of the tower.

Trafalgar House – 180 East 70th Street

(KPF – Kohn Pedersen Fox, 1986)

At Trafalgar House, Kohn Pedersen Fox (KPF) embraced traditional imagery to project the aura of history, permanence, and luxury of classic Upper East Side apartment houses. The 33-story Edwardian Georgian-inspired tower is clad in red brick and topped with a triple-pedimented crown. Trafalgar House is Postmodern for the way it imitates the style of classic Upper East Side apartment houses at a monumental scale, pasting historical ornament onto the once-austere high-rise to create a building that looks new but feels historic.

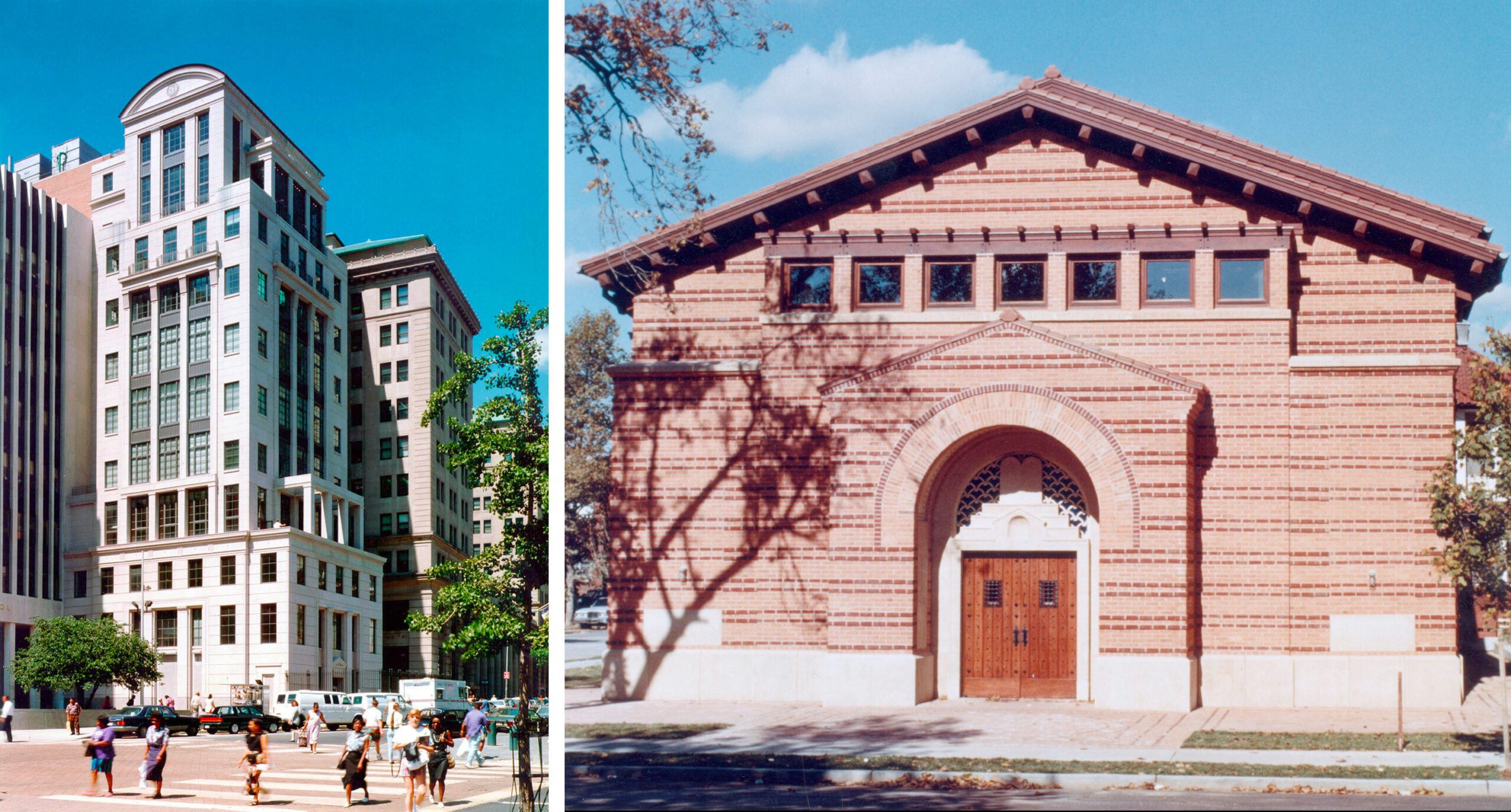

Kol Israel Synagogue, 3211 Bedford Avenue, Brooklyn, NY (RAMSA, 1989)

Postmodernism didn’t just borrow from ancient Greece and Rome. Set in a residential East Midwood neighborhood of free-standing houses, Stern’s Kol Israel Synagogue riffs on the Mediterranean-inspired architectural features popular in nearby homes. Exposed rafters under a clay tile roof, medieval-looking wood doors topped by an almost Moorish tympanum, decorative bands of brickwork, thick wood window mullions, and ornamental nail heads reflect the historical roots of the synagogue’s Sephardic congregation.

Brooklyn Law School, 250 Joralemon Street, Brooklyn, NY (RAMSA, 1994)

It is no surprise that as an advocate for recognition of Postmodern architecture today, Robert A. M. Stern’s portfolio includes some excellent Postmodern designs of his own. Stern’s addition to the Brooklyn Law School is emblematic of his practice. Borrowing from Classical architectural styles, the eight-story pre-cast concrete bell tower features pediments, medallions, triglyphs, and a post-and-lintel pavilion all reinterpreted in a modern way.

1001 Fifth Avenue (Johnson & Burgee, 1977-79)

Located within the Metropolitan Museum Historic District

Postmodern architecture seeks to be playful and even ironic in its use of traditional architectural features. It can also be deferential to its context in a way that Modernism was not. Philip Johnson and John Burgee’s 1001 Fifth Avenue achieves both. The residential building towers over Museum Mile with columns of grey-tinted windows and pewter gray metal spandrels, but its most recognizable feature is a large parapet wall that resembles a mansard roof from the front. However, viewed from the side it is clearly a free-standing imitation. The mansard makes reference to the adjacent 19th-century buildings already on Fifth Avenue. This building was a turning point in Johnson’s career and set the stage for his design of 550 Madison Avenue, one of the most recognizable Postmodern buildings today.

Jewish Museum expansion, 1109 Fifth Avenue

(Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo & Associates, 1993)

Felix Warburg Mansion was landmarked in 1981; landmark report predates Roche Dinkeloo addition

In stark contrast to Johnson & Burgee’s high-profile Fifth Avenue intervention, Kevin Roche’s expansion of the Jewish Museum is a historicist scheme bereft of the irony other Postmodern buildings employ. Roche created a seamless extension of Charles Gilbert’s landmark 1908 French Gothic-style Felix Warburg Mansion that could easily be mistaken for part of the original building. Here, being contextual and respecting the existing history of the site was the priority.

Ballfields Cafe, Central Park

(Buttrick White & Burtis, 1990)

Located within Central Park Scenic Landmark

The Ballfields Cafe, was inspired by Calvert Vaux’s demolished ball players’ pavilion, with contrasting bands of red and light-colored brick relating the color and material of this new structure to its predecessor. Upon close inspection, the building’s geometric tile frieze, intricate latticework, angular-patterned and contrasting red and grey slate, and aluminum cresting are abstracted versions of Victorian ornament. This intimately-scaled building adapts Postmodernism to a park setting.

Charles A. Dana Discovery Center, Central Park

(Buttrick White & Burtis, 1993)

Located within Central Park Scenic Landmark

The Charles A. Dana Discovery Center rounded out the restoration of the Harlem Meer’s romantic 19th-century landscape. A variety of verge-boards, arches, pendants, brackets, and its cross-gabled roof give the building its picturesque character, but also identify it as a modern addition to the park.

135 East 57th Street (KPF, 1988)

Unusual for New York City, Kohn Pederson Fox’s 135 East 57th Avenue doesn’t build to the property line, but has a concave façade. This novel massing carves out an open plaza at the street corner. The building has several classical elements, but the round, columned temple in the plaza is the most notable feature. The almost whimsical structure manages to anchor and define this corner in the busy Midtown urban landscape.

Permanent Mission of India to the United Nations, 235 East 43rd Street

(Charles Correa, 1992)

Charles Correa’s design for the Permanent Mission of India to the United Nations highlights the diversity of the architectural traditions that Postmodern architects drew from. The narrow, 24-story tower’s bold geometric forms—including a stepped terrace covered by a Cubist pergola, a reference to open-air sleeping areas called barsati—are mixed with massive but intricately detailed wood and brass doors made by Indian craftsmen.

110 East 64th Street (Agrest and Gandelsonas, 1984)

located within the Upper East Side Historic District

The design of 110 East 64th Street was determined largely by the existing context of the site. This residence is flanked by two buildings that illustrate Postmodernism’s taut position between tradition and modernity: to the east is the Gothic facade of Henry C. Pelton’s Central Presbyterian Church and to the west is the modernist glass and steel facade of Philip Johnson’s Asia House. The husband-and-wife team of Diana Agrest and Mario Gandelsonas dealt with this site by erecting a six-story classicized design that acts as a bridge between the two larger structures.

Leonard Stern townhouse, 870 Park Avenue (RAMSA, 1975)

Located within the Upper East Side Historic District

Another example of Postmodernism applied to a residential use is 870 Park Avenue, the Leonard Stern Townhouse. An early example of Postmodern design, the building was one of Robert A.M. Stern’s first commissions. At 870 Park Avenue, pilasters and a distinguished balance of ornamental proportion imbue this spare modern facade with a classical, dignified air that allows it to work contextually with the Upper East Side’s architecture.

750 Lexington Avenue (Helmut Jahn, 1989)

Occupying the entire west blockfront from 59th to 60th Street in one of Lexington Avenue’s boldest Postmodern office buildings: Helmut Jahn’s 750 Lexington Avenue. A series of dramatically arranged setback masses of blue-tinted glass and steel wrap a cylinder that emerges at the top and telescopes into a conical pyramid that supports a sphere in a design that Paul Goldberger called “a wonderful, even witty piece of inadvertent dialogue in the cityscape.”

425 Lexington Avenue (Helmut Jahn, 1988)

Helmut Jahn’s stubby, 30-story chamfered tower of glass, marble, and buff granite at 425 Lexington Avenue rises from a substantial base and flairs at the top to resemble a classical column. Jahn’s design received little praise from the critics and public, overshadowed as it was by the venerable landmark Chrysler Building just across the street. Nonetheless, the strong colors and unusual but symbolic forms are hallmarks of Jahn’s practice and Postmodernism as a movement.

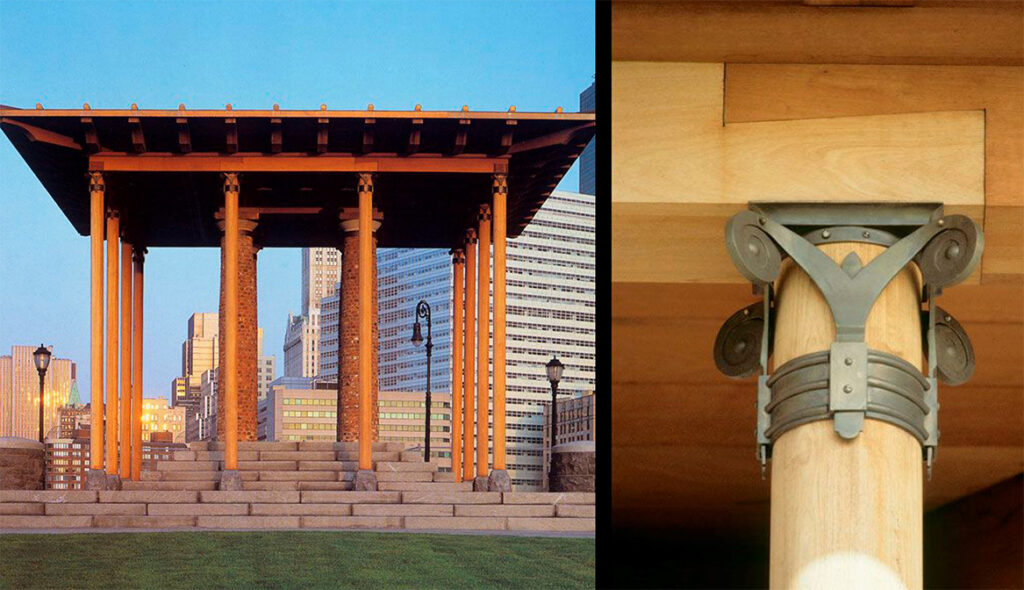

Battery Park City, Lower Manhattan (Alexander Cooper

Associates, 1979) including The Upper Room (Ned Smyth, 1986) and Pavilion (Demetri Porphyrios, 1990)

Built atop 92 acres of landfill generated by the construction of the World Trade Center and dredging the harbor, Battery Park City is New York’s first Postmodern master plan. Reflecting a renewed preference for urbanism, Stanton Eckstut and Alexander Cooper of Alexander Cooper Associates (the firm was later renamed Cooper Eckstut & Associates) laid out a mixed-use community linked by cohesive and interdependent architecture, replete with housing, plazas, and parks featuring iconic Postmodern art spaces like Demetri Porphyrios’s Pavilion and Ned Smyth’s The Upper Room.

World Financial Center – 230 Vesey Street (Cesar Pelli, 1988)

Cesar Pelli’s World Financial Center, the planned nexus of Battery Park City, is a Postmodern Rockefeller Center. Fourteen acres of plazas, gardens, restaurants, and a steel-and-glass framed Winter Garden are grouped around a harbor and surrounded by four square towers clad in glass and granite. The towers are differentiated by distinctive rooftop features—a pyramid, a stepped pyramid, a truncated pyramid, and a low dome. Pelli’s design also showcases Postmodern architecture’s revived respect for the existing urban fabric; the towers themselves are stepped in height from the water.

Worldwide Plaza Tower – 825 Eighth Avenue (SOM, 1989)

Worldwide Plaza Residences – 350 West 50th Street (Frank Williams, 1989)

Worldwide Plaza is another significant Postmodern development that has left its mark on New York’s skyline. A team from Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill led by David Childs, designed the 45-story office tower, and Frank Williams designed the accompanying apartment building. The full-block complex includes a park and other amenities that attempted to create a tiny urban neighborhood on a site that had most recently been a parking lot. The base of the office building is a prime example of Postmodern classicism. However, seen from a distance, the recycled architectural language of both buildings seems to come less from the ancient world and more from the city’s own skyscrapers of the 1920s and 1930s, with pyramidal roofs, vertical shadowlines, and setbacks.

Philip Morris Building – 120 Park Avenue (Ulrich Franzen, 1983)

At first glance, the Philip Morris headquarters is a boxy Modernist-looking office building, but a closer look reveals architect Ulrich Franzen’s careful attempts to be respectful of the building’s urban context and incorporate some classical details. The building’s massing is intended to relate the lower floors to its formidable neighbor directly across 42nd Street, Grand Central Station. A large carved medallion (now removed), simplified columns, and classical proportions also identify the building as Postmodern.

Four Seasons Hotel – 57 East 57th Street (I. M. Pei in association with Frank Williams, 1992)

The slender limestone tower of the Four Seasons Hotel was I.M. Pei’s first New York City skyscraper. The building was designed in association with Frank Williams and built between 1988-92. The result of the architects’ collaboration is a luxurious mix of Postmodern historicism and flashiness: the building is dotted with angular glass lanterns, ornamented window lintels, chamfered corners, and a dramatic entrance topped by an empty stone circle. The tower’s massing is harmonious with the Art Deco Fuller Building next door: the height of the base exactly aligns, the upper floors feature numerous setbacks, and the main entrance is announced by an exaggerated height among the flanking window openings.

U.S. Courthouse Annex – 500 Pearl Street (KPF, 1994)

In 1991, Kohn Pedersen Fox was tasked with designing the U.S. Courthouse Annex at 500 Pearl Street, and the result of their efforts was is a Postmodern blend of modern and classical elements. Designed to align with Cass Gilbert’s United States Courthouse (1929-36) with a lower structure that matched the height of Guy Lowell’s New York County Courthouse (1927), the Annex’s granite skin and repetitive window arrangement distill the classical elements of the historic buildings around it into something contemporary and contextual.

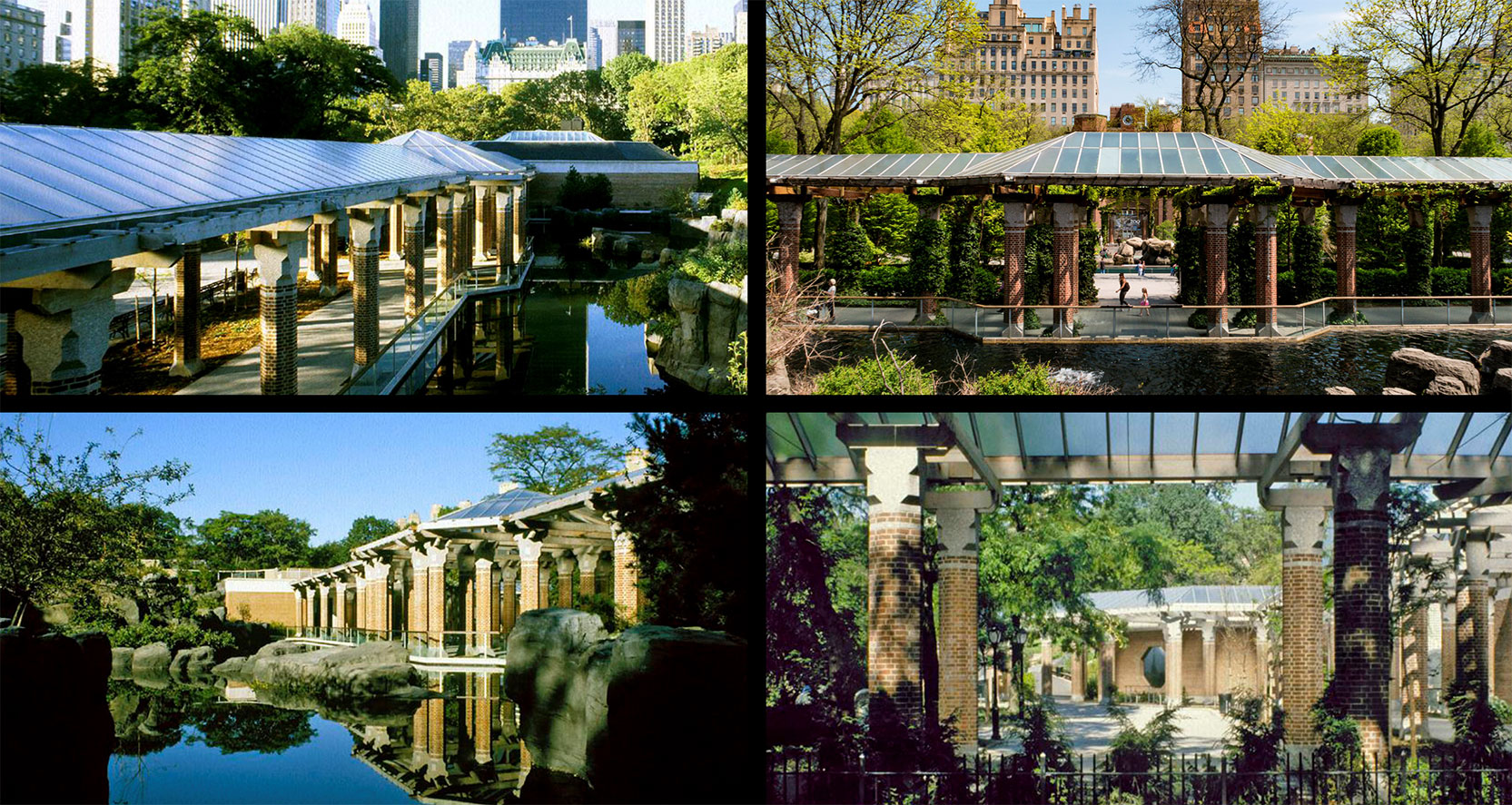

Central Park Zoo – East 64th Street

Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo & Associates, 1988

Located within Central Park Scenic Landmark

Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo & Associates’ redesign of the Central Park Zoo managed to integrate three existing buildings and several beloved artworks all within a famed scenic landmark. The new design added three new buildings and linked them to the existing structures with columned arcades. The firm often used chamfered columns in their work. Here the columns are brick with faceted limestone capitals, which Roche dubbed as being of the “zoo order.”

Museum of Jewish Heritage – 36 Battery Place

Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo & Associates, 1997

After several decades and several different architects, the Museum of Jewish Heritage finally opened in 1997. Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo & Associates designed the six-sided building with a ziggurat-like roof located on the Hudson River at the southern end of Battery Park City. The six facades and six tiers of the roof are meant to represent the six million lives lost in the Holocaust as well as the Star of David. The original building was meant to accommodate expansion, and in 2003 a Roche-designed addition that curves around the original building was completed.

Thank you for helping us save the very best of the City we love.